In recent years, scientists have made huge progress in furthering our understanding of how the immune system works, and applying this knowledge to vaccine design. Yet we are still pretty much in the dark about what makes a “good” vaccine. Are live replicating microorganisms better than dead ones? Is it better to generate an antibody or a T cell response? Are central memory or effector memory T cells better?

Big data promises to help us get to the bottom of these questions, and ten thousand others just like them. By analysing huge data sets, we can begin to tease out correlations and signatures that predict if (and how) a vaccine will protect against its designated disease.

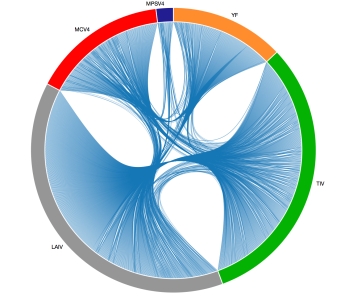

Scientists at Emory University recently took the big data approach and created a hugely powerful database loaded with the molecular profiles of over 30,000 human blood transcriptomes from ~500 studies. They used this to look for a signature of protection across 5 successful human vaccines (2 against Neisseria meningitidis, 1 against yellow fever virus and 2 against influenza virus).

Since their tested vaccines varied in their nature – some were conjugate vaccines made up of two distinct parts, while some were live attenuated vaccines – it was tricky to come up with a universal vaccination signature between all 5 vaccines beyond the basics of “B cell activation” or “leucocyte differentiation”. Happily, though, it was possible to see similar signatures of immunogenicity within a vaccine class. For example, vaccines that had a large carbohydrate component tended to induce stronger T cell responses, while live attenuated vaccines upregulated larger innate immunity and interferon responses.

In the image above, genes responding to each of the 5 tested vaccines (red, blue, orange, green, gray) are represented as segments of the circle. Bigger segments contain more differentially-expressed genes. A link between two segments indicates an gene overlap between vaccines.